There's nothing quite like a quiet class four road on the flanks of Sterling Mountain in Johnson, Vermont, on a cool, cloudy morning in early June. I have the road to myself, accompanied by my golden retriever Blaze, who'll be five in two weeks, and my trusty old black lab Blue, who turned twelve in April.

Pausing on a big grade, I look into the forest. The canopy is fully deployed, ferns spread like a soft feathery cushion. I see paths, creeks, and glimpse into that land of the heart and soul—full of ghosts and memories and smells and animal scat.

It seems uninhabited, but everywhere life is going on. Salamanders crawl across fallen logs. Deer flies ready themselves for their murderous rage, coming any time the heat returns. Soon this place will become unwalkable. Mosquitoes lurk, waiting. Snakes hide in the underbrush. Elk roam these woods, along with deer and bear—I've seen all of these up here, though not often. The bear was just a cub, halfway up a big tree, staring at me terrified. I thought about his mother possibly being nearby and backed away quickly.

But this is a quiet place, and the cool air makes my exertion tolerable. The lack of mosquitoes or deer flies buzzing around my face is a massive bonus.

In dog years, Blue is effectively eleven years older than me, and Blaze is going to be thirty-five, half my age more or less. So Blaze does what his name suggests: blazing his own trail. Blue steadily keeps pace with me, usually ten yards ahead, sometimes three, occasionally a little behind. Just like our aging golden retriever Izzy, who died five years ago this summer, old man Blue is starting to exhibit the same signs— pausing, staring off into space, sniffing the air, seemingly lost in reverie, perhaps triggered by scents on the breeze.

My wife used to say that Izzy was getting Alzheimer's, but I like to believe he was just pausing to remember, a memoirist in his own way. Like the last time we took him to the waterfall—he was too weak to scramble down the bank, so I carried him. He was down to nothing but skin and bones, half of what he used to be. I sat him down in the shallow water. It was so hot that day, July 18, 2020, a month before he died peacefully in the wee hours, resting comfortably his spot on our leather couch.

Izzy and I had a deep bond around water. I remember when we'd swim in the lake—I would plunge my cupped hands and make big booms. He would try to bite the water as it erupted. If I had a hose, he would try to bite the stream, going almost nuts for it. That last day, I gently splashed some water toward him, and he looked at me like, "I remember, but I can't do anything right now, Dad. But I remember."

As we age, memory is all we have left. There are no more wild blue yonder dreams, just that space you can find on a deserted class four dirt road in Johnson, Vermont, early on a cloudy morning.

Father's Day 2025

Sitting here at the top of an amazing waterfall, watching my dogs navigate at their different ability levels—Blaze getting into all kinds of trouble, Blue just taking it all in from the edges.

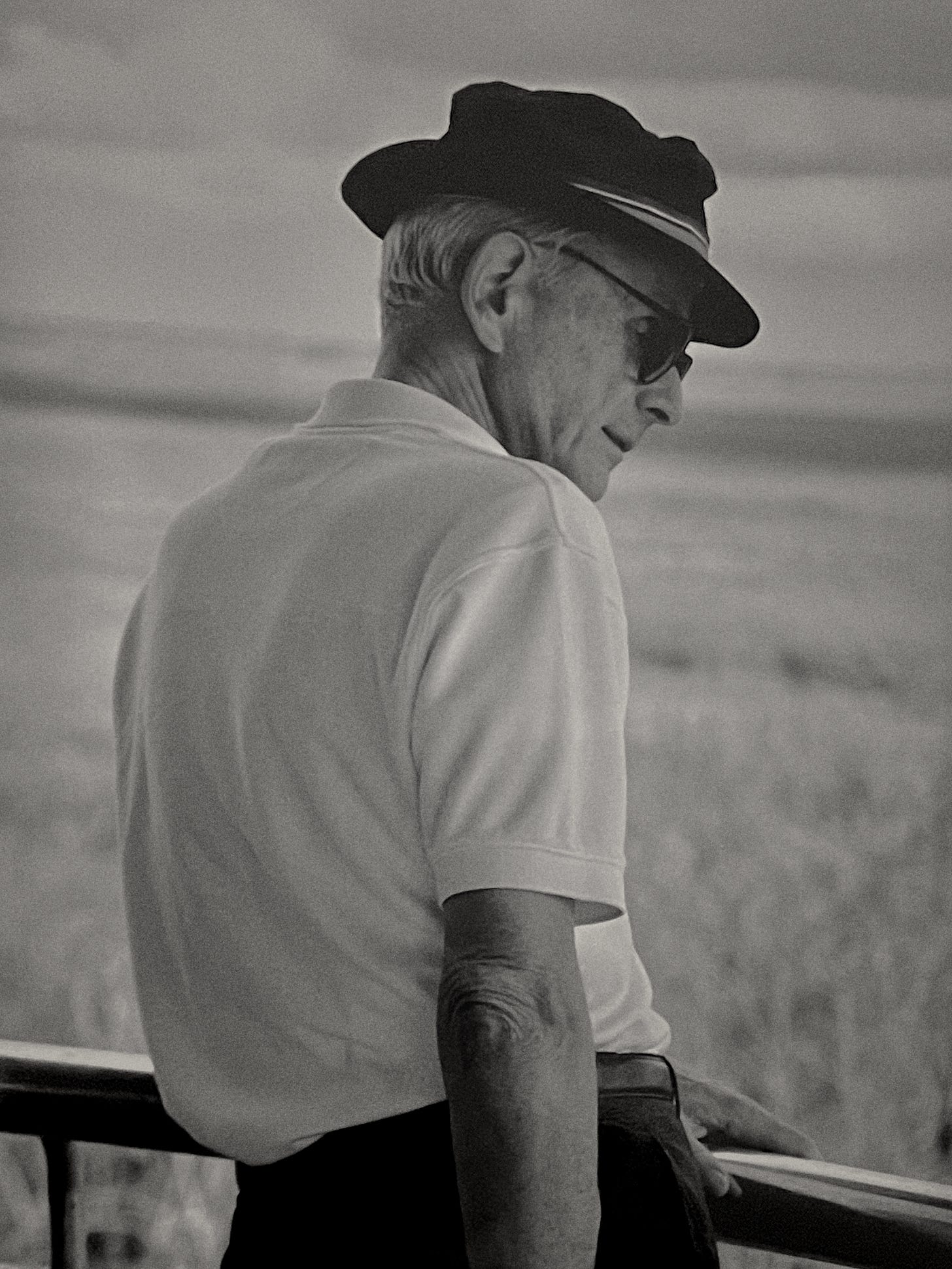

I remember my father. When he would telephone me, or when I called him, he always answered the same way: "André, my boy." There was definitely still affection there right to the end and I regret our estrangement.

He died three years ago this month at ninety-four. It had been just shy of fifty years since the sale of our 1865 farmhouse on 25 acres on a dirt road in Armonk, New York. During the first twenty-one years of my life, he was a dominating figure. Then he more or less disappeared.

I think we both held wounds we couldn't forgive. But I always felt his shadow through those fifty years of estrangement—that judging voice. It was the voice of a trainer disappointed that his yearling didn't turn out to be the champion he'd hoped for. He looked at me as someone who had broken a trust, maybe.

All our issues came to a head after I dropped out of the college he made me go to instead of the college I wanted. He told me, "André, if you ever go back to school for a year on your own and get a B average or higher, I'll pay for it."

Five years later, when I got into USC after attending San Francisco State for a year on my own—working full-time, earning a B-plus average—I contacted him to see if he'd help like he'd promised. He said he had no money.

Meanwhile, he was buying racehorses, had hired a trainer, was living in a really nice place in New York City. He shortly moved to one of the cushiest suburbs of Seattle, bought a huge place, tried to become racing commissioner. He had the money. He just wanted to punish me. We human beings can all be like that, petty and vindictive, with a long memory.

It's taken me three years after his death to see this and forgive him. But I was just a child when he did all that to me. Even though I wrote him a long letter in my forties detailing all my issues with him and “forgiving” him—because I was told it would be healing—he wrote back saying he'd been busy raising six kids, blah blah blah. Now, looking back, I realize that must have been awful ordeal for him too.

It was just a bet he'd made, raising six kids, and when it didn’t pan out, he simply walked away. Despite it all, I have a renewed sense of sympathy and love for my father—we're all human. We all have sensitive parts of our souls and hearts that, once bruised, don't seem to bounce back.

Giving each other forgiveness and space, trying to walk a mile in each other's shoes, goes a hell of a long way toward finding peace in our own hearts—not letting this stuff eat us alive, push us into addiction, or worse, self-harm and violence.

Nature has a deep heart, and I'm in the middle of it here with my dogs at the top of a beautiful waterfall. I thank the universe for this moment because it's rich and deep and priceless. You can't order it online, can't download it, can't really give it away. You can try to share it, but I have it. It's mine. It's my moment of peace.